Seifert, Krysta. “Essay: Trained elephants kill followers of Khan Zaman.” In The Akbarnama: A Digital Art History Student Project, April 4, 2018. .

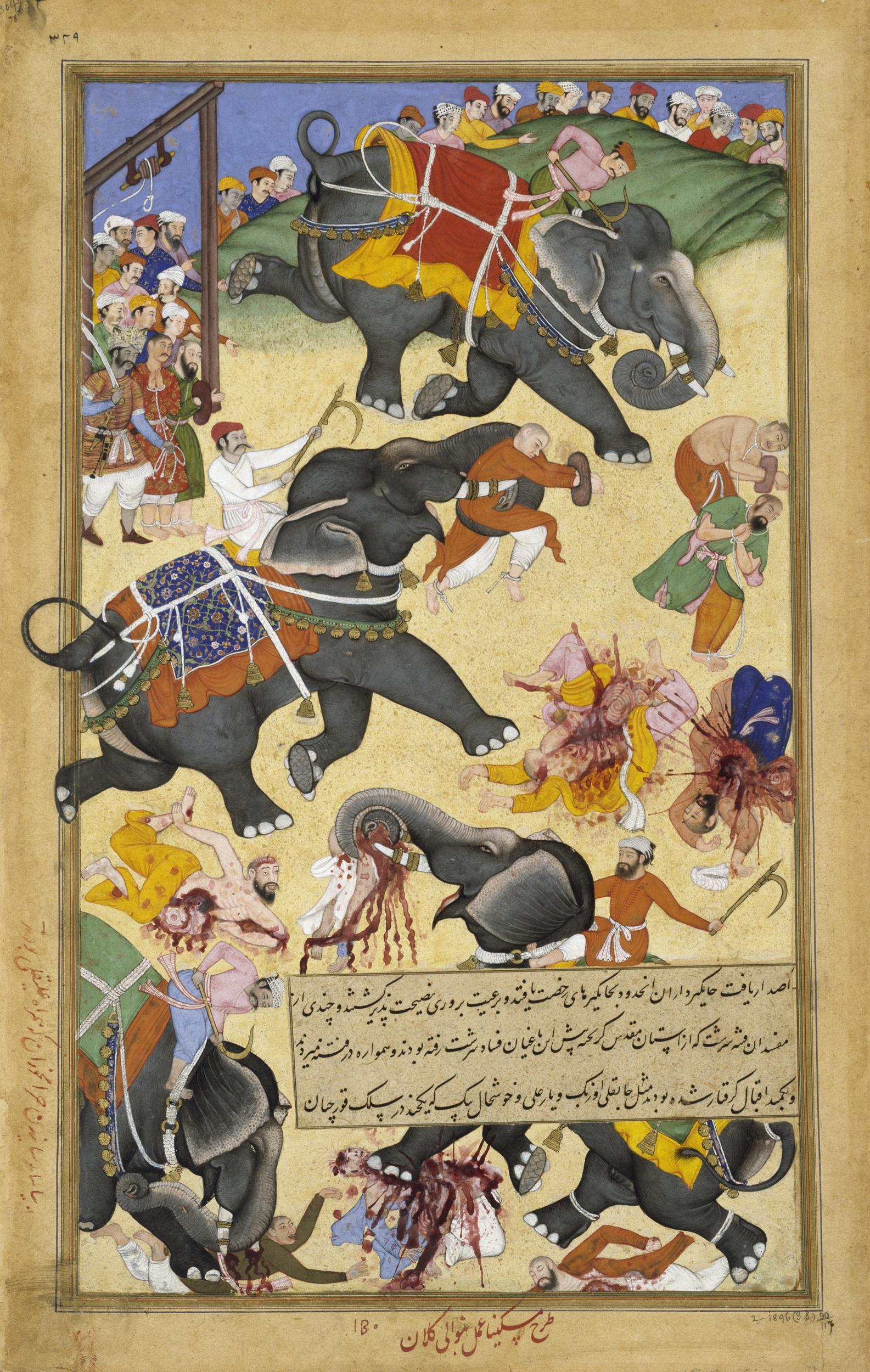

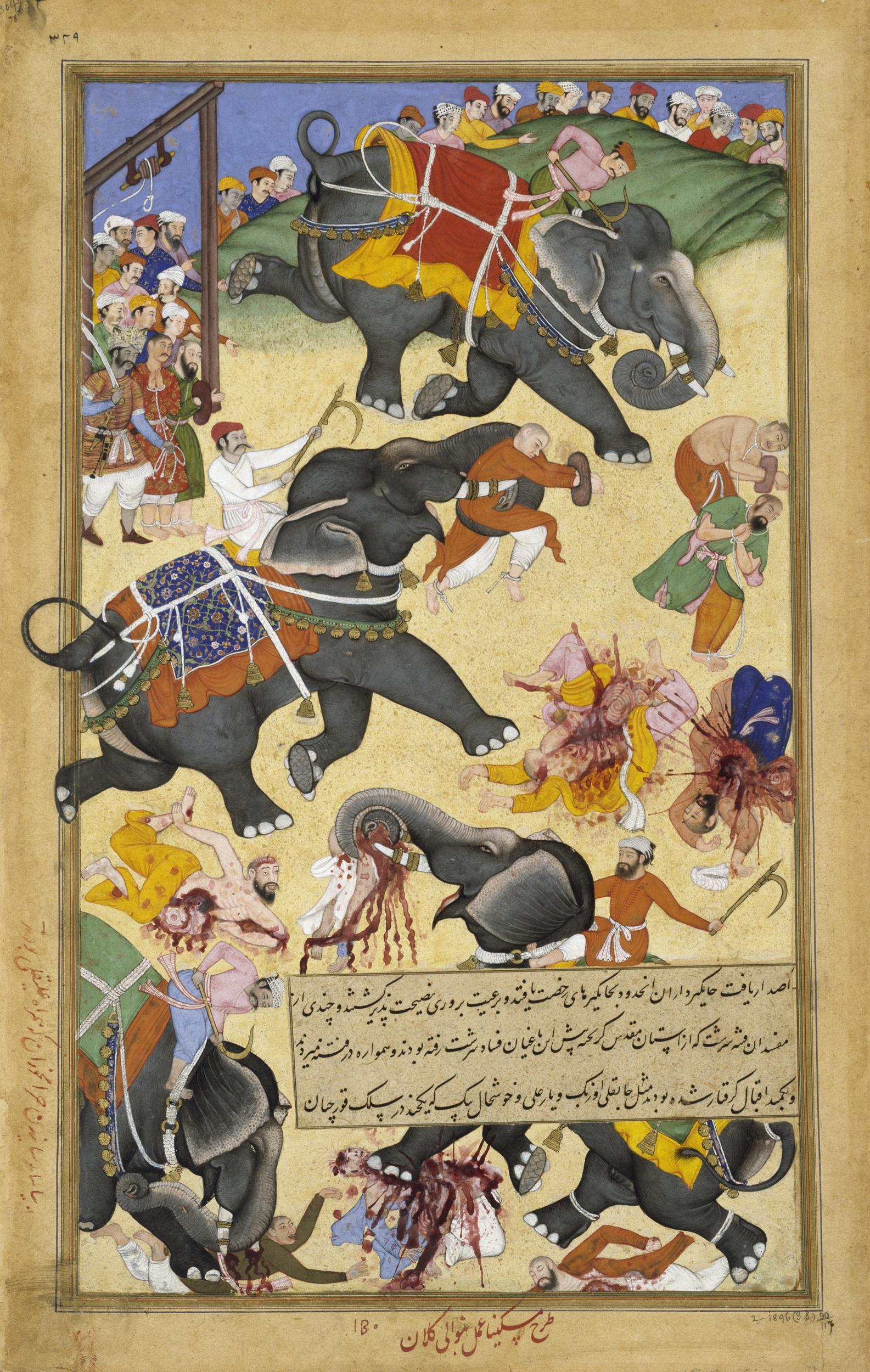

The Akbarnama, or Book of Akbar, is an account of Mughal Emperor Akbar’s reign as recorded by his court historian and biographer, Abu’l Fazl. It was written in Persian, and the manuscript is accompanied by painted illustrations using opaque watercolour and gold. This vast project was undertaken by a team of the finest artists and calligraphers of the time, who engaged in a division of labour until its completion. Folio 90 of the second volume of the Akbarnama was outlined by court artist Miskina and painted by Banwali between 1590 and 1595. It is currently housed in the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, England among many other miniature paintings from the Akbarnama. Folio 90 depicts followers of Khan Zaman as they are executed by elephants on Emperor Akbar’s orders. The scene takes place in northern India at Karra in 1567 following the execution of rebel-leader Khan Zaman.

Ali Quli Shaibani was a soldier under the rule of Akbar’s father, Humayun. After Humayun’s passing, Shaibani proved himself a brave and valuable warrior in Akbar’s early military campaigns and thus was granted the title ‘Khan Zaman’ as well as a plot of land for his valiant efforts on behalf of the empire. Unfortunately, Khan Zaman’s loyalty frequently wavered after his title was bestowed, and it was rumoured that he intended to rebel against the empire (Sharma 195). Khan Zaman also engaged in a tumultuous love life which included a homosexual affair with a bodyguard of the Mughal court, Shaham Beg, as well as sexual exploits involving a threesome, and marriage to a prostitute (Chatterjee 66). This blatant disregard to Akbar’s power, as evidenced by his disrespect for the customs of the times, did not sit favourably with the emperor (Chatterjee 66). As one might imagine, Khan Zaman’s insubordinate behaviour did not quell the rumours of rebellion, but rather reinforced them. Eventually his indiscretions both in the bedroom and on the battlefield could no longer be tolerated by Akbar, and so he was brutally executed. As Fazl later recounts in the second volume of the Akbarnama, "he was [hunted down and] trampled under the foot of the elephant, or rather, under the weight of his sins and ingratitude" (433).

Mirza Rezavi Mirak, also called Mirza Mirak Mashhadi, was a follower and close companion of Khan Zaman. In fact, Mirak was so trusty a companion, that he stood up for Khan Zaman in front of Akbar’s court and pleaded for his life, a scene which is depicted in Folio 89 of the Akbarnama. By this point in time, in 1567, Khan Zaman had rebelled outright, thus confirming the rumours of his disloyalty. Despite this, Mirak was able to convince Akbar to forgive him this once and granted him the opportunity to make peace (Sharma 196). However, Khan Zaman proceeded to rebel yet again, and so following his death, Akbar set his sights on squashing the rest of the rebel uprising, believing Mirak to be a guilty party in all of this because of his close ties with Khan Zaman. As such, Mirak and other followers were captured and sentenced to death in Karra. In Folio 90, Mirak appears dressed in green and awaits his turn with the elephant while all other comrades are quite literally squashed around him. After all other insurgents were dead, the elephant grabbed Mirak and tossed him around; the bloody corpses of his mates lying about in plain sight. In the Akbarnama, Fazl explains that “a clear sign for his execution had not been given [by the driver]," and as such, "the elephant played with him and treated him gently" (436). Rather than give Mirak a swift death, Akbar allowed for the elephant executioner to taunt him in this manner for five consecutive days before deciding to spare his life (Fazl 436).

Akbar the Great held elephants in high regard, going so far as to assign them a position of honour in his palace and implementing a breeding program for those in captivity (Hart and Sundar 35). During the Mughal reign, elephants were considered so crucial to the success of an emperor’s army that the names of both individual mahouts and elephants became celebrated and well-regarded in the same manner as any other renowned combatant on the battlefield (Fazl 60). In preparation for war, elephants were trained to remain at ease in the presence of battle noises, such as canons and gunfire, as well as to wear armour and wield weapons attached to their trunks (Schimmel 92). Their use extended beyond war, however, as they also stood as testament to both the power and spiritual enlightenment of the ruler who used them successfully (Allsen 157). Trained elephants served as evidence that the emperor could tame wild beasts, thus exhibiting his command over more than just his human subjects and imbuing him with divine power for all to worship and obey (Allsen 157).

The role of a mahout is to tame and train the elephant, a relationship which usually begins at a young age and often continues through the lifespan. The unique human-animal connection that is established between mahout and elephant over the course of this relationship’s development is crucial to the training of both parties. Elephants are trained not only to auditory directions, but also to the body language and foot movements of the rider, even specifically to the rider’s tone of voice (Hart and Sundar 36). In sum, the elephant is trained to respond to the mood and commands of the mahout, in effect directly under his control (Allsen 156). Such a training paradigm worked well in accommodating last-minute gestures of compassion and this indeed was a strategy of Akbar the Great. As evidenced in the story of Mirak’s near-execution, a mahout may signal to the elephant at any time to stop, even when or if the victim is an inch from death. Akbar seemed to favour this technique as it placed him in a supreme position of power and accomplished the two-part goal of teaching a lesson to rebels and earning their unwavering gratitude (Allsen 156).

Elephants were commonly used as a means of capital punishment during the reign of the Mughal Empire (Schimmel 96). They were chosen over other wild beasts for the fact that they were easily trained, making them swift and obedient deliverers of justice and divine retribution (Allsen 156). As depicted in the folio, often the victim’s hands would be tied, and this enabled the elephant to pick up the wrong-doer by the arms and toss him around for a while before trampling him to death (Schimmel 96). Apparently, the thought of this was dreadful enough to entice many facing execution to commit suicide before elephants had a chance to ‘play’ with them (Schimmel 96). That Mirak faced this awful experience for five days straight perhaps speaks to his bravery and character despite having fallen prey to the wiles of suspected rebel, Khan Zaman. Furthermore, these execution events were staged for public viewing as a method of deterrence from criminal and insurgent behaviour (Allsen 156). This is keenly evident in the folio, as people seem gathered around the boundary of the execution ground watching in both horror and awe at the top of the painting.