Haque, Omi. “Essay: Akbar & Hamid Bakari.” In The Akbarnama: A Digital Art History Student Project, April 4, 2018. .

Before getting in to the description of this piece in the Akbarnama, a bit of background is necessary. This will be to accommodate the motifs, zeitgeist and aesthetic direction of the times. In artistic representations an important aesthetic value was accorded to the principles of formal linear harmony and symmetry through which human agency would impose its own order and stylization on nature, so as to draw out its beauty and to intensify the experience and enjoyment of it by those privileged to do so. The Mughal emperors spent considerable portions of their lives , during their frequent journeys, military and hunting expeditions, in direct contact with nature. This provided the occasion for pictorial narratives to work their way through different idioms that would communicate the idea of a fine ecological balance between the imperial body and the land. The intrinsic presence of violence and mutually hostile forces within nature, a continuing struggle for power and survival, was a continual theme privileged by artists- a favourite topos was the portrayal of powerful animals devouring the weaker ones.

The motif of a lion killing a gazelle, or a rabbit or a bird or a bull or at times even a human being was a recurring one. Intervention in this struggle involved domestication of threatening forces and an imposition of order, balance and harmony through curbing nature’s unruliness. Once domesticated animals come to acquire humanized expressive qualities and serve metaphor for perfect justice adl 29.

The subject of the hunt, a favourite of Mughal artists, centred on some of these issues, though pictorial practice did register shifts here while trying to accommodate different understandings of the hunt. Many different meaning and functions have been ascribed to the hunt in north Indian political culture; alone in Mughal texts the list valorizing the hunt beyond being simply a favourite royal pastime is a long one, and visual representations moved over time between privileging one or the other. In many parts of early modern Asia hunting was endowed with special significance as an attribute of rulership. Francois Bernier, the French traveller to Mughal India in the seventeenth century, described a successful hunt as being a “favourable omen,” as the escape of an animal was a portent of “infinite evil to the state” (cf. Bernier 1992, p. 379). Among the Hindu kings of early medieval India, the ritual of enthronement (rajyabhiseka), the placement of the imperial body at the sacral centre of the kingdom, was enacted with the throne set over five skins of hunted animals, those of a wolf, a civet, a leopard, a lion and a tiger (cf. Inden 1998, p.74).

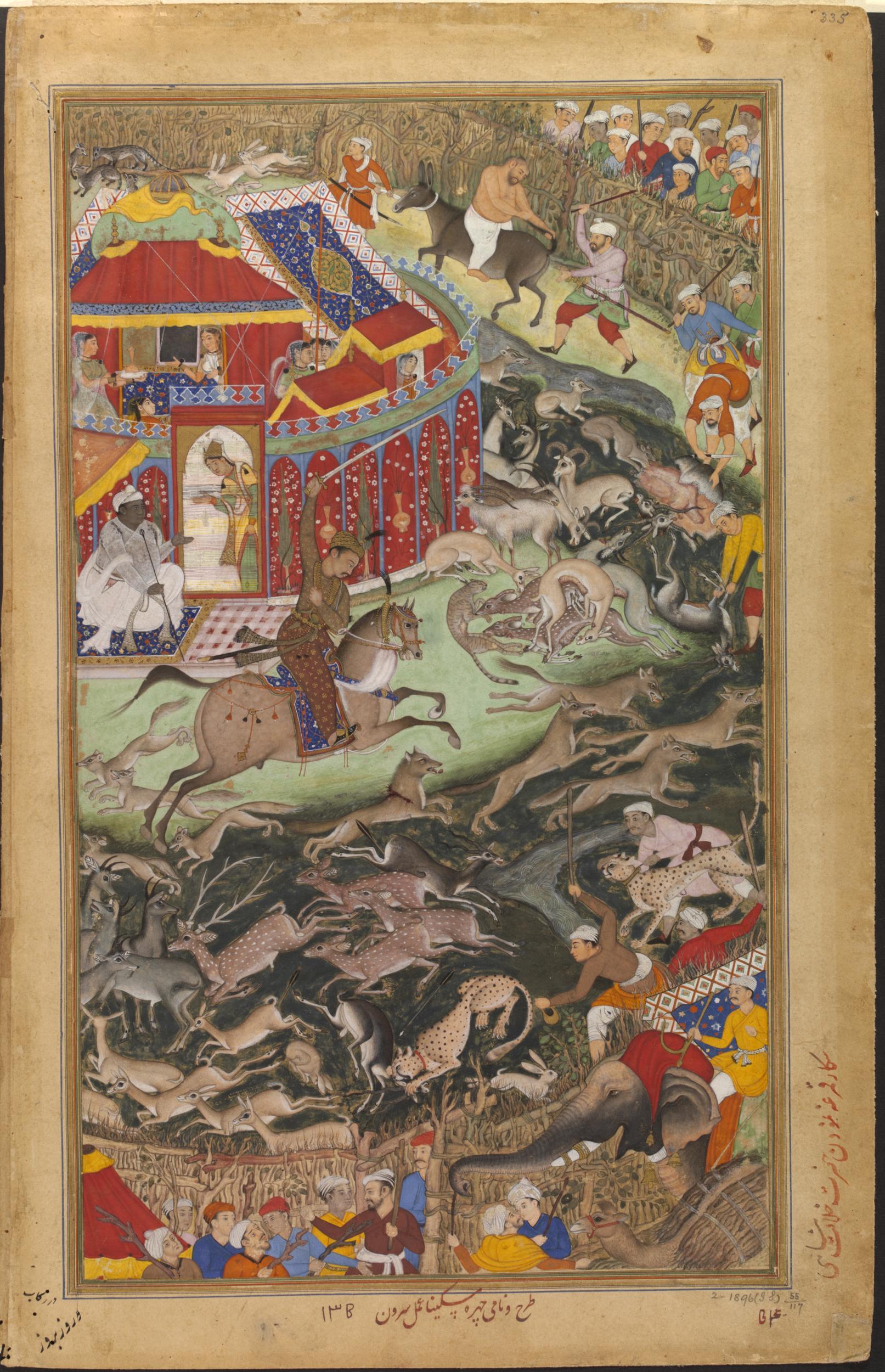

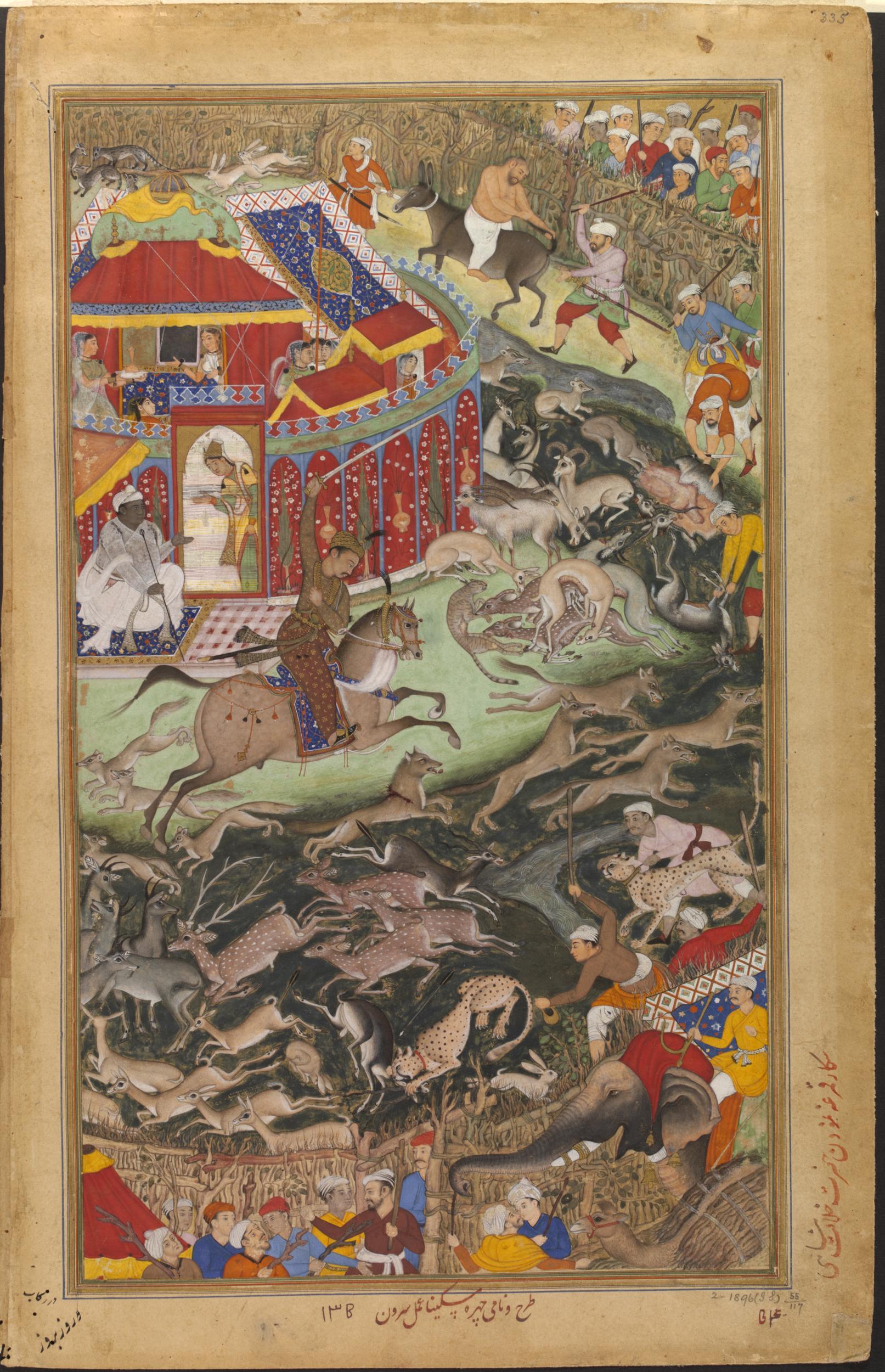

In the double page miniature portraying a hunting scene from the Akbarnama, the artists Miskin and Mansur focus primarily on the bodily relationships between the hunting emperor, the hundreds of beaters, torch bearers and other helpers, and an equally large number of animals all contained within a composition which locks man and nature within swirling movements. Yet the image also contains a clear ideological reference to the virtue of justice: its upper right hand edge makes space within the hunting enclosure for an incident that had taken place int he Akbarnama (Vol. 2, pp. 417f.). A certain Hamid Bakari had committed an offence against a court official. The punishment meted to him is part of this image, symbolically the site of justice: the culprit is shown head shaved off, mounted on an ass being taken around the hunting area as an act of public humiliation. Hunting in this sense has been described as a form of bodily action that brought the emperor regularly to far flung regions of his empire, enabled him to keep an eye on his subjects, and gain knowledge about their condition (cf. Akbarnama, Vol. 2, pp. 417f.;Koch 199, p. 12). The relationship between bodily action and spiritual purpose is articulated in images in which Akbar is portrayed as experiencing a moment of mystical communion and enlightenment in the midst of a hunt.

The entire composition depicts a ceremonial hunt that took place near Lahore, in present-day north-east Pakistan, in 1567. Here, Akbar is seen taking part in a Qamargah, which is a spectacular hunt whereby the game is driven towards the centre of a ten mile circular area so that the emperor and his entourage could hunt and kill the animals. It is one of the finest hunting scenes in the V&A Akbarnama paintings and features the early work of the artist Mansur, who became one of the greatest Mughal artists.

The Mughal emperor Akbar is shown in the centre of the painting mounted on horseback with his sword raised. An order was issued that birds and beats should be driven together from near the mountains on the one side, and from the river Bihat (Jilham) on the other. Several thousand footman from the towns and villages of the Lahore province were appointed to drive the game. A wide space within ten miles of Lahore - like the capacious heart of princes- was chosen for the collecting of the animals. At the beginning, the hunting ground was ten miles in circumference. But day by day the Qamargah was pushed on and its area lessened. There was pleasure from morning till evening and from evening till morning.

The Rajput noble Dhanji got 4 to 5 lashes from Akbar’s whip when he said that he could not report to court on time as he was dressing up. A young Rajput prince Prithidip, who was playing nearby with his advisers/ attendants with the permission of his uncle, also received lashes from Akbars whip. Upon Being whipped, the Rajput noble Randhirot, unable to bear this insult to himself at the hands of the Emperor’s servant, repeatedly stabbed himself in his stomach and killed himself before Akbar. Instead of being shocked by the act, Akbar was further enraged seeing the ‘audacity’ of this Rajput, and ordered the dying Randhirot to be trampled by an elephant, saying - “Kill this bastard!”. All in all, the Qamargah was a true bloodbath of man and beast.

Images of the hunt from the mid-seventeenth century shift to a more contained, or resolved, idiom which resorts to increased naturalism to locate the physical imperial presence within the heart of nature, in greater harmony with the land and its flora and fauna, as in painting from the Windsor Badshahnama. Embedded in the receding image, is a scene of a peasant working on the land, while another draws water from a well. Their distant bodies merge with nature and the colours of the earth, conveying an unmistakeable message of harmony and resolution effected by an imperial power in perfect control over a realm that encompasses the land, its plant and animal life and the bodies of the subjects that work it.

The variety of pictorial experiments to create images that worked as both of the body and those which stand for the body, had the power to function across regional identities in more than one way: ethnic and pluri- religious imperial elites in north India during the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and could equally be reappropriated by these to define anew the boundaries between the empire and the regions. The dynamic accelerated with the transition to the eighteenth century, a time marked by imperial disintegration and the emergence of new political formations, country and market cultures, processes which all have been competently analyzed by historians over the past decades. These years were also a time of cultural shifts, when court artists sought employment with new patrons espousing different forms of political and bodily cultures- the Marathas, Sikhs, the Deccani elites, now joined by the trading officials of the East India Company. Examining the ways in which visual cultures participated and constituted the historical fortunes of these decades promises to be an exciting and rewarding undertaking.