Jonas, Emma. “Essay: The Death of Adham Khan.” In The Akbarnama: A Digital Art History Student Project, April 4, 2018. .

The Victoria and Albert Museum in London, England is home to many preserved paintings from the Akbarnama, an illustrated manuscript detailing the life and reign of Mughal emperor, Akbar. The Akbarnama is home to many intricate folios painted by renowned artists of the Mughal court to accompany each story of its text. They feature numerous examples of Mughal stylistic conventions in Indian art and calligraphy.

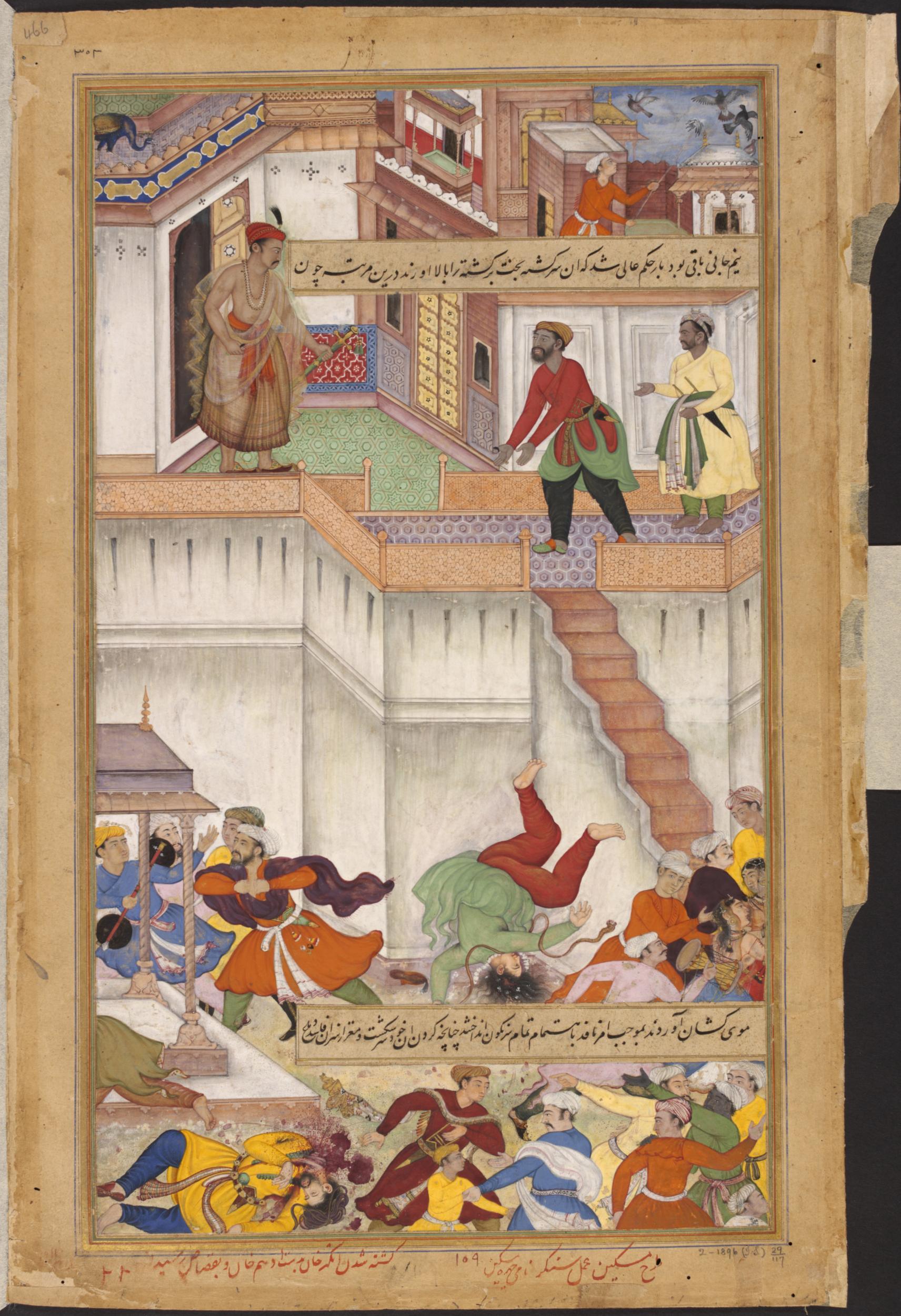

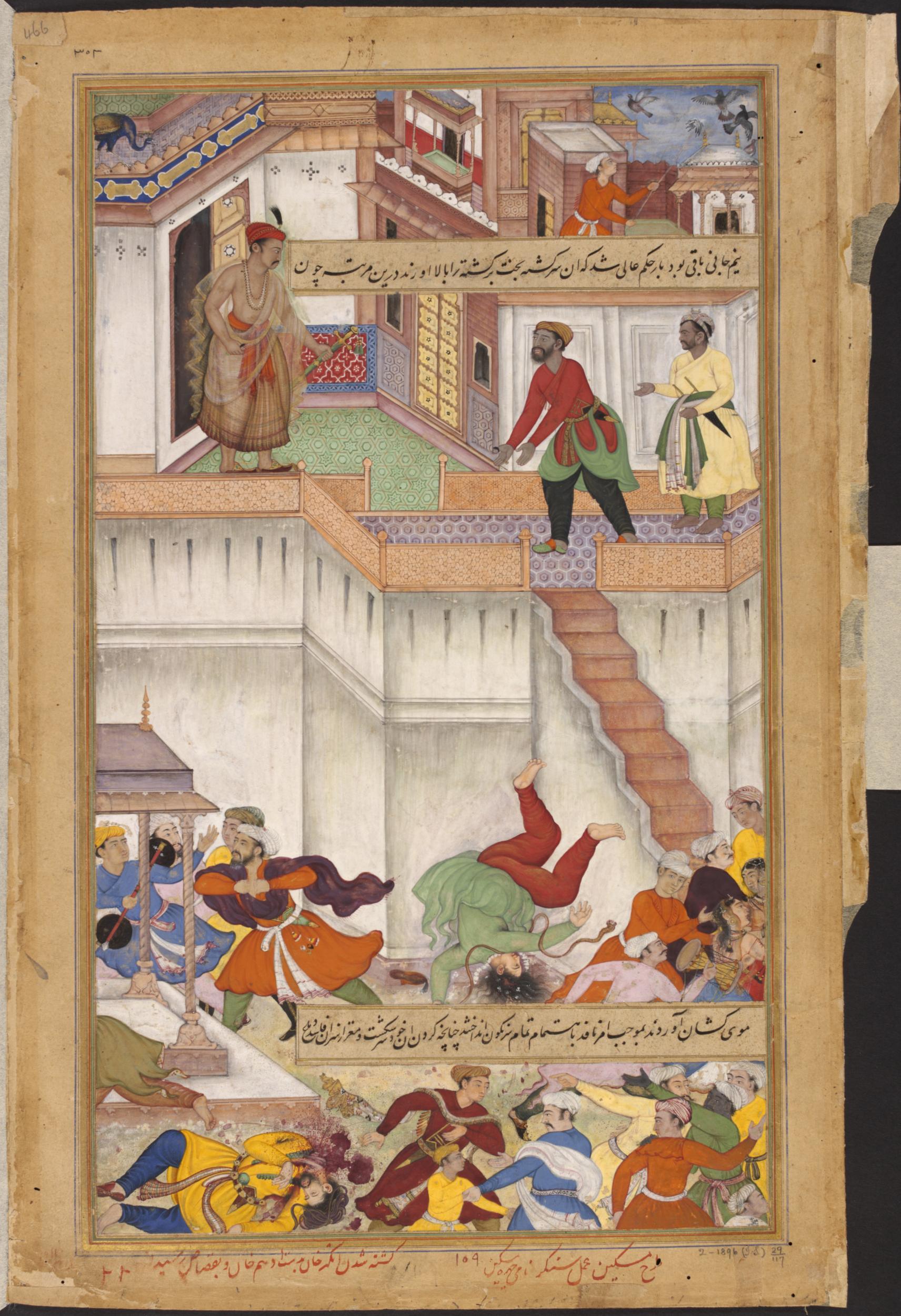

Amongst the V&A’s collection of illustrations from the Akbarnama is “Adham Khan thrown from Agra palace walls”, painted by Miskin and Shankar. The painting depicts a chaotic scene from the Akbarnama’s second volume. In the top-left of the image, Akbar stands wearing brown robes watching as his two servants, wearing red and yellow, have just thrown Adham Khan off the palace terrace. Akbar’s expression is unfazed in a confident and assertive manner. Downstairs, Adham Khan has fallen head first to his death. As the focal point of the painting, Adham Khan is still in dynamic posture as his head is just beginning to hit the ground. Members of the Mughal court scatter from the fall in fear and despair. In the bottom-left of the painting lies the dead Ataga Khan, who has blood spilling from the slash marks on his chest. In the top-right of the painting, a servant is shooing away a group of birds and is seemingly unaware of the turmoil below.

There is a sense of horizontal line and separation within the image that not only depicts hierarchy but guides the viewer’s gaze from top to bottom. There are many intricate decorations and reverse perspective within the architecture of the Agra palace that exemplify the artists’ attention to detail. Three lines of calligraphy decorate the painting along with a brown border surrounding the folio.

Akbar is known as one of India’s greatest emperors. His grandfather, Babur, founded the Mughal empire. However, Akbar is renowned as the one who made the Mughal dynasty as successful as it was. Since his father, Humayun, passed at an early age, Akbar became heir to the throne at age thirteen. Given the amount of time that he was exposed to the Mughal government, Akbar was able to make decisions that would benefit the people and their respected beliefs. His goal was to unite Hindus and Muslims, and he believed that all religions should be treated equally. Therefore, the Mughal empire turned into one that was home to numerous people with many different religious preferences. A dynasty with religious tolerance was unheard of during its time.

The Akbarnama is an illuminated manuscript from the Mughal empire. Commissioned by Akbar himself, it was first written in Persian in the late 16th century by Abul Fazl and later translated to English by Henry Beveridge. It was divided into three volumes. The first volume described the lives of his predecessors, as well as his birth. The second volume is specific to Akbar’s reign of the Mughal dynasty. The last volume, named Ain-i-Akbari, featured details of the administrative aspects of the Mughal empire (Seyller 380).

Adham Khan was the son of Maham Anga, who was Akbar’s chief nurse. Maham Anga was very close to Akbar and Adham Khan was considered Akbar’s foster brother. They thought of each other as family. Adham Khan was even appointed to general of the army after Bairam Khan was dismissed. During his time in the army, he was known to make hasty and uncontrolled decisions. Despite this, Akbar continued to have Adham as general.

When Akbar appointed Ataga Khan to prime minister in place of Mu’nim Khan, this thoroughly upset Adham Khan and his mother. Adham grew jealous of the Ataga Khan while being further provoked by Mu’nim Khan (Welch 255). Mu’nim was furious that he had been replaced, so he planted dark ideas in Adham Khan’s mind.

“Intoxicated by youth and prosperity” (Beveridge 269), Adham Khan and his two accomplices belligerently entered the royal hall where Mu’nim Khan, Ataga Khan, Shihab al-Din Ahmad Khan, and other magnates were conducting public business (Welch 255). Adham Khan ordered his servants to take action. First, servant Kusham Uzbek stabbed the chief sitter on the pillow of auspiciousness. Then, before Ataga Khan could escape, servant Khuda Bardi struck him twice with his sword, killing him in the courtyard of the hall of audience (Beveridge 269). Adham then quickly fled the hall and searched for Akbar, who was resting upstairs. Having heard the mayhem downstairs, Akbar met Adham Khan on the veranda. Adham attempted to grab Akbar by the hands but was quickly met with a blow to the head from the fist of Akbar himself, knocking him unconscious. Soon thereafter, Akbar sentenced Adham Khan to death for his reckless and fatal actions. He was tossed from the Agra palace terrace by Akbar’s servants. Surviving the first fall, Adham was then brought back upstairs and thrown off the terrace for a second time, leading to his death.

It is notable that the large expanse of miniatures accompanying the Akbarnama’s text are stylistically cohesive, despite being painted by many different artists. The attention to detail in the buildings, decoration, and clothing are significant; scholars have often have used paintings from the Abkarnama to document Mughal material culture and architecture (Seyller 379). When analyzing “Adham Khan thrown from Agra palace walls”, the depiction of the architecture is accurate and intricate. The use of shading creates depth and spatial recession within the structures while exhibiting a realistic stone texture. Reverse perspective is used to bring the accuracy in all elements of the architecture to light. A clear example of this is the small building just behind the servant in the top-right corner of the image, where the back end of the building is disproportionally longer than the front. The convention of reverse perspective is popular within Christian Byzantine art, proving that the Mughal court painters were influenced by many different styles of painting. Amongst many Mughal paintings in the Akbarnama and other illuminated manuscripts, a special attention to detail is given to the patterns on the floors, walls and mouldings. This further gives historians the ability to picture exactly what the structures had looked like in their prime.

While the movements of figures are depicted with lifelike accuracy, it is almost as if the architecture and design of the buildings were given more importance than human faces. The actions of the figures and their clothing are dynamic and have realistic qualities, however, they are not entirely naturalistic. Most faces are oval-like and lack distinction. Akbar is identifiable for his notorious moustache; however, without it his face would not be recognizable. Instead, Mughal artists use other forms of identification like specific clothing or auras to distinguish important characters from other figures. Furthermore, ancient calligraphy is placed throughout Mughal paintings. The painting is organized strategically around the text to ensure the viewer can see the scene without being distracted by the calligraphy. The conventional brown border as well as the limited colour palette further give the paintings within the Akbarnama a sense of unity.

The death of Adham Khan was an important event during Akbar’s reign. Adham challenged Akbar and forced him to make a difficult decision that went against his own family. Despite this, Maham Anga respected his choice. Akbar sentencing Adham Khan to death proved to members of the court that he would not allow family or friends any leeway when they committed crimes. He continually commanded respect from the Mughal empire. Akbar never ceased to put the empire and his people first, proving once again that he was one of the greatest emperors to ever rule in India.