Alli, Mikhail. “Essay: Ali Quli, Bahadur Khan and Akbar.” In The Akbarnama: A Digital Art History Student Project, April 4, 2018. .

The Akbarnama miniature paintings is a collection of artwork that were commissioned by Akbar himself towards the end of the 16th century. Painted by artists from his own court and all of India, the miniatures provide a great insight into Mughal life and medieval India during Akbar’s reign. The subjects of the miniatures range from events, places, people, architecture, flora and fauna that was encountered by Akbar. What is also interesting in these paintings is that much can be learnt not from the miniature subjects itself but rather from the specific work or painting as a whole. Painting styles of various artists of various backgrounds tells us that there is a circulation and fusion of multiple cultural traditions, from various times. Like a photograph, these paintings truly allow us to locate ourselves and comprehend that particular period of the South Asian history.

It was during Akbar’s reign that art truly prospered and flourished in the subcontinent. He was a patron for the arts, much like his father and grandfather before him. Akbar had a curious nature to him, and his eye for aesthetics really contributed to his support for the advancement of the arts. Akbar’s reign had a certain characteristic that allowed for extensive cultural advances. His toleration and intrigue of other cultures and religions allowed for the assimilation of many styles of art. Although Humayun and Babur too were tolerant of other traditions, Akbar had simply conquered more of India enabling him to learn and assimilate a more diverse set of practices from more provinces. Unlike Humayun’s reign for example where paintings followed a Persian style, paintings from Akbar’s reign contain fusion of Indigenous Indian and Persian styles, with certain western influences due to European presence in India in his time.

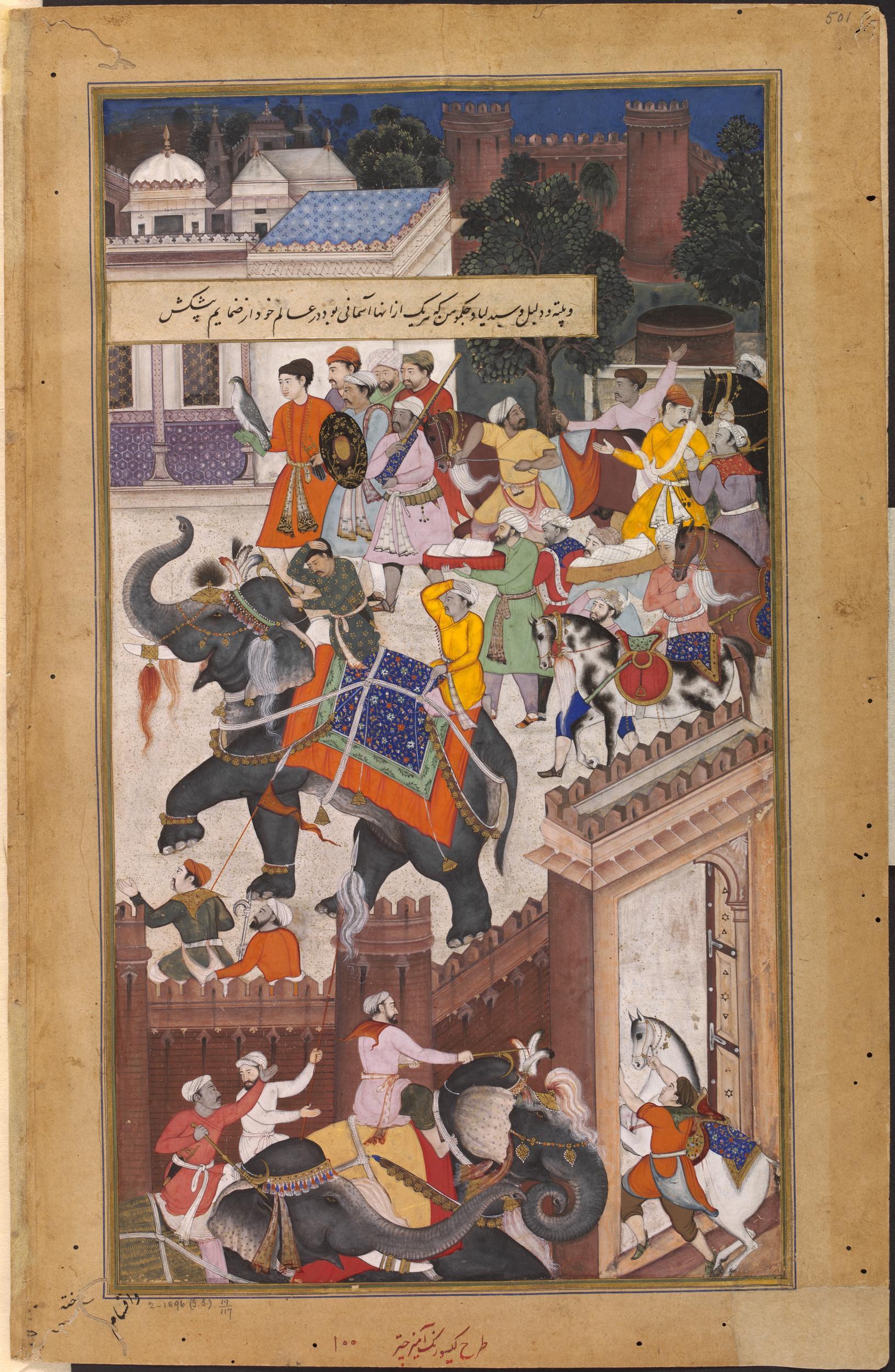

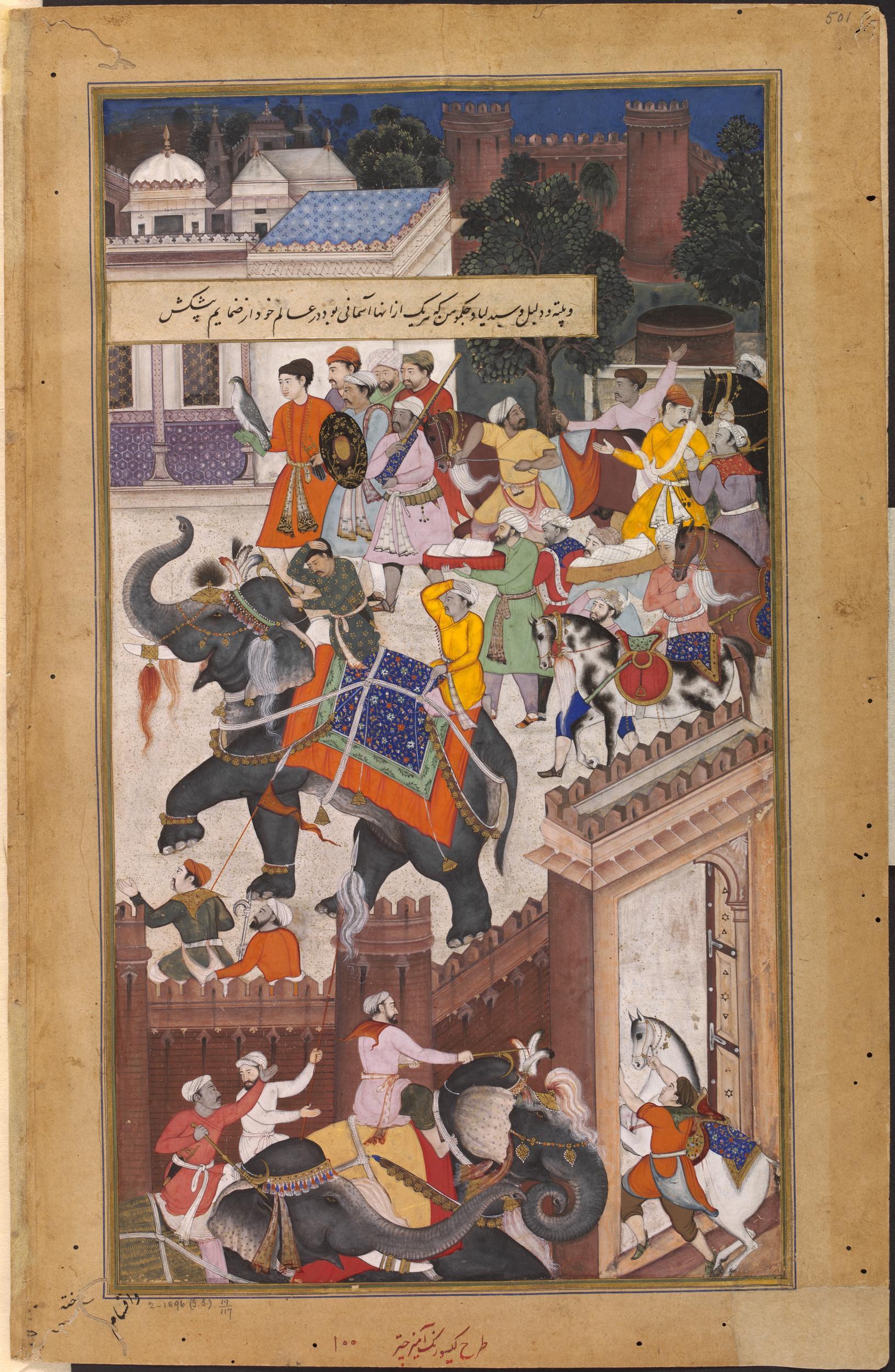

This painting, sourced from the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, shows the interaction between the emperor Akbar, Bahadur Khan and Ali Quli Khan. This painting represents only the right half of a larger picture. Although Akbar is not physically present in this painting, he appears in the left half, this miniature does however show the other two figures. The two figures here, shown entering the gated compound on elephants, with their hands holding their heads in shame and regret are Ali Quli Khan and his brother Bahadur Khan. Although they were Mughal officers, they were nobles from the Turkish Uzbek faction under Mughal rule. The Uzbeks had a reputation for being the most untrustworthy of all Mughal officers due to their faction’s traditional antipathy towards Babur and his lineage (Mehta 1984). The event that is depicted here was the brothers submitting to the emperor after going against his orders.

The story of the painting was that during the Afghan insurgency, the brothers were ordered to face the rebel army at Jaunpur. Upon succeeding, instead of sending the war booty back to the central court, the brothers had lied about the contents of war loot keeping most of it to themselves (Chandra 2006). When he found out that the Uzbek brothers had disobeyed his commands, Akbar made a force march towards Kara where he hoped to disgorge the brothers of their treasures. Upon Akbar’s arrival in Kara, the brothers grew frightened of the possible consequences they may face so without further delay, the brothers made their way to the nearby city of Kara with the elephants and treasures they had acquired after their battle (Chandra 2006). As depicted in the painting, the brothers arrived carrying a regretful expression. There they paid homage to the emperor and were forgiven by Akbar’s merciful nature.

The falcon that can be seen in the upper left of the painting carries a heavy significance in Mughal-Turkic culture. The presence of the Falcon itself especially in paintings signify power and signals the presence of the rulers. Falcons were seen in this culture as imperial birds, a tradition that had been in use by their Turkish ancestors (Malecka 1999). According to Anna Malecka, these imperial birds symbolized sun, light and royalty. These birds were regarded such attributes due to their fearless and glorious nature, flying incredibly high above all the other birds, close to the sun. It is of no coincidence then that the Falcon appeared in this painting, in the presence of the emperor. As Malecka pointed out, the Falcon symbol tradition was also seen in several earlier Timurid paintings that portrays the passing down of power from one ruler to his descendants suggesting that the Falcon may also symbolize Timurid heritage.

Native to the Indian subcontinent, elephants were a common sight Mughal Paintings. These majestic beasts were highly utilized animals that served many roles from warfare, to executioner, entertainment and to assuming great prestigious roles at court (Malecka 1999). Due to their intelligence and size, and especially their ability in warfare, elephants were glorified and was also a symbol power and strength (Malecka 1999). Due to this, domesticated elephants were treated better than most people of the time, having at least a few servants each. It was not uncommon for elephants to be seen or depicted as wearing expensive and beautiful fabrics, adorned with expensive ornaments. In her book The Empire of the Great Mughals: History, Art and Culture, Annemarie Schimmel describes the elephants as “caparisoned in red velvet embroidered with gold brocade, and adorned with silver chain and cords, often ornamented with precious stones and, most importantly, different sized bells” which is somewhat a near accurate description of the elephant in the painting though without the red velvet. It is also curious to observe that all riders on the elephants were carrying a goldish hook-shaped tool, which in her book revealed to be an elephant goad, used in training and handling the animal (Malecka 1999).

Another point of interest is perhaps the architectural design that can be observed in the painting. Red sandstone used for the walls and towers were common building materials in India. The white domes were characteristics of middle eastern Islamic architectural style. Also, if we look much closer onto the walls and floors, we can see a very specific form of decorative patterns and imprints. The patterns that can be seen here, on the tiles and mosaics, for the most part is geometrical in nature. In the architectural article by Yahya Abdullahi and Mohamed Rashid Bin Embi, geometrical patterns have been in used by Islamic cultures as an architectural decorative element for centuries (Abdullahi and Bin Embi 2013). Observing closely, we find that the most common geometrical patterns used in the painting were 6 point patterns known as the hexagon. It is unclear whether the 6-point pattern was the most common design throughout the empire but however, it was pointed out in the article that Mughal Architects rarely went above 12 points, commonly utilizing 6,8 and 10 geometrical point shapes (Abdullahi and Bin Embi 2013).

The same floral patterns that seem to decorate fabrics worn by men, elephant and the horses also makes for an interesting observation. In his book, Fabric Art: Heritage of India, Sukla Das points out that floral patterns were Islamic in nature, originating in Persia then brought to India by the various cultural interactions. This new pattern, used and valued by the Mughals then replaced the previous Indian styles which utilized more animal and human figure motifs (Das 1992). It isn’t much of a surprise then that floral patterns became dominant under Mughal rule when we consider the appreciation that Mughal emperors had for garden and nature.