Walters, Aravis. “Essay: Akbar Tiger Hunting in Narwar.” In The Akbarnama: A Digital Art History Student Project, April 4, 2018. .

The Akbarnama is a biography of Akbar, who is arguably one of the greatest Mughal emperors of all time. It was written by Abu Faz-l in the 14th century and illustrated by a variety of court painters, outliners, and calligraphers. It is written in Persian, the written language of the Mughals. The Akbarnama has three volumes.

The first volume focuses on the birth of Akbar, the history of his ancestor Timur’s family, and the reigns of his predecessors: Babur, his grandfather and the founding father of the Mughal Empire, and Humayun, his father.

The second volume, in which in this painting is found, describes Akbar’s life and his reign.

The third volume, called the Ain-I-Akbari, described the administration of the empire, Akbar’s household and army and many other details. For example, it describes with great specificity such things as crop yields.

The second volume is the most important in understanding who Akbar was as a person, and how he portrayed himself to his people.

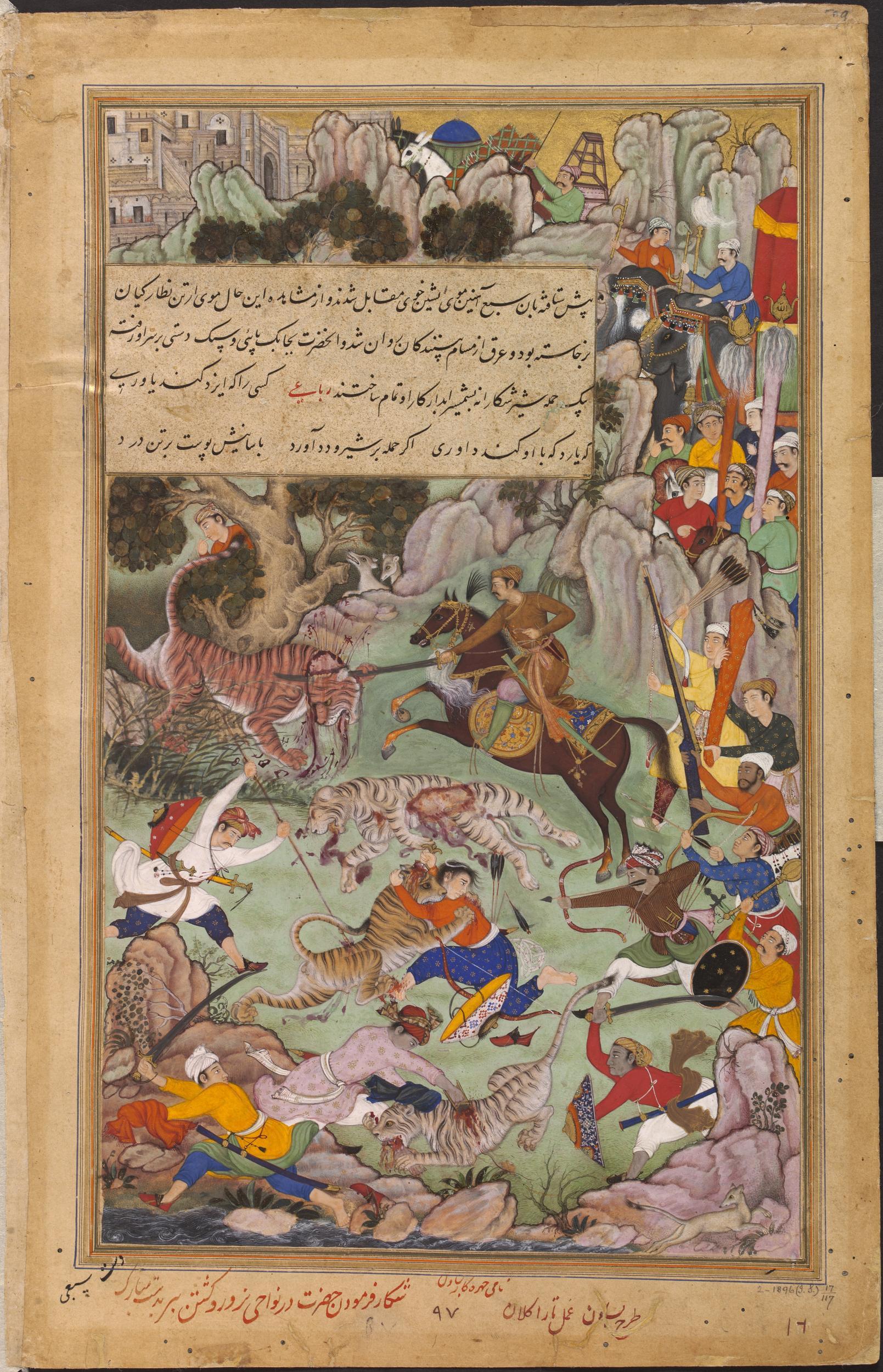

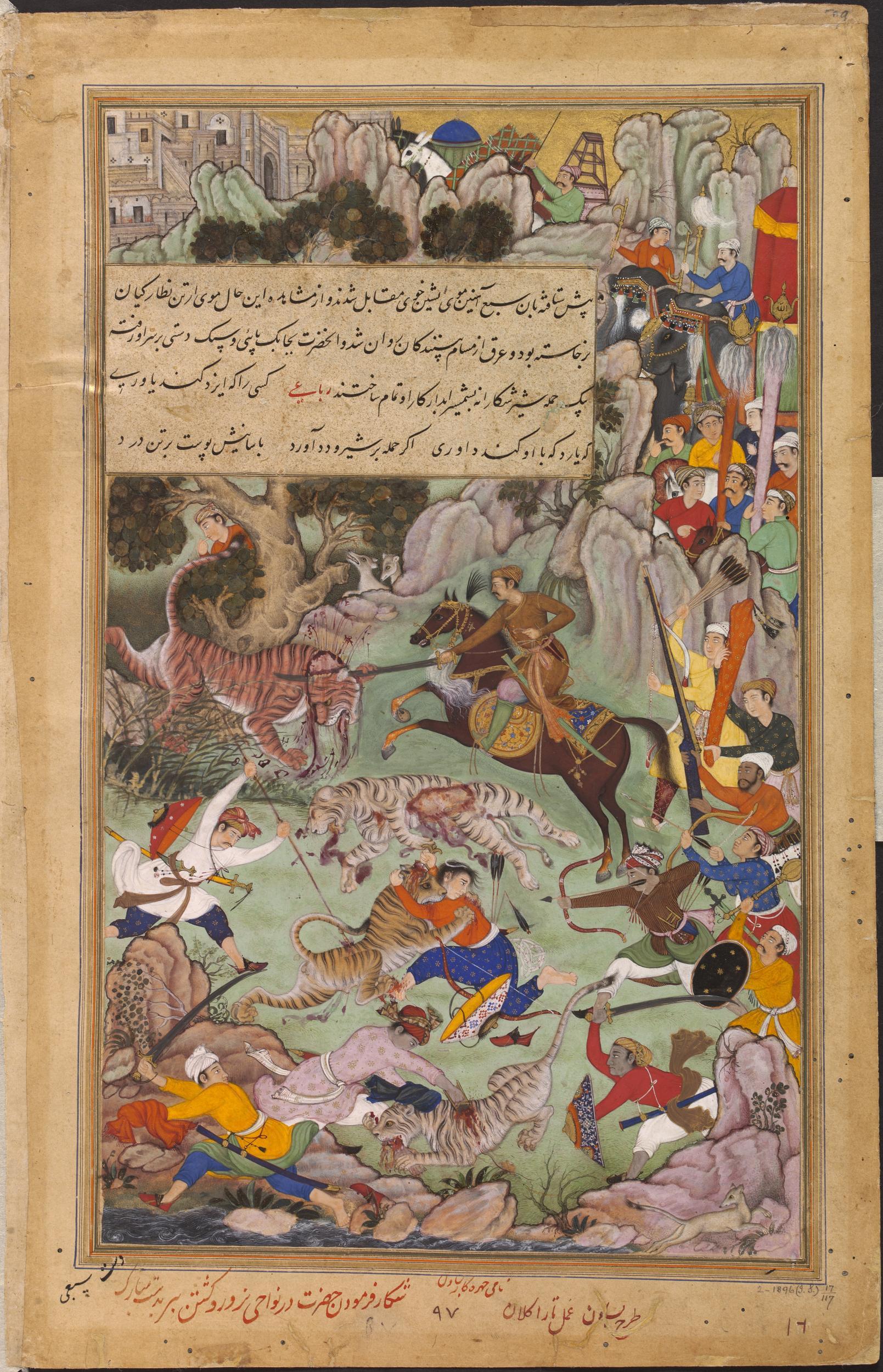

This particular painting depicts Akbar on his way through the Gwalior district of Narwar, India. He and his cavalcade were hunting on their way. However, they accidentally disturbed a mother tiger and cubs from their den. In anger, the tigress and her cubs attacked the party. According to the Akbarnama, Akbar, being the mighty emperor that he was, spurred his horse towards the fearsome beast and beheaded her with one stroke of his sword. Abu Faz-l describes him as having “The strength of the Lion of God in his arms, and the coat of mail of the Divine protection on his breast” (Akbarnama, 22). At the same time, his soldiers fought and killed the tiger cubs. Almost singlehandedly, Akbar saves his people from great harm in this moment.

This painting and its accompanying story is an excellent example of the way Akbar uses art and story to portray himself as a caretaker of his people. This awesome display of bravery—leaping forward alone to confront a giant tiger head on—proves that Akbar takes care of his people and protects them from various evil or dangerous forces around them (Pandian, 91). Akbar uses paintings and deeds like this to convey this important quality about himself and ensure the trust of the people (91). The actual act of hunting was also often used as a metaphor for the strength of the emperor and his ability to subdue predators (90). Akbar’s hunting prowess directly translates to his might and skill on the battlefield. His willingness to face great danger to protect his hunting party shows to what lengths he will go to protect his loyal citizens. This painting conveys to anyone who sees it how Akbar cares about his people and protects them at all costs.

Not only does this painting display Akbar’s character, it also gives the modern viewer an important and fascinating look into Mughal weaponry. Many typical arms are on display in this scene. For instance, many of the men are shooting arrows at the tigers from a distance. Mughal Indian bows were composite weapons, made of wood, gut, and horn (de la Garza, 68). Most archers carried two bows—a light one for when on horseback, and a larger one for on foot. Most of the men in this painting would be using a heavier one as they take aim at the tigers from behind various rock outcroppings. Another, lesser used type of bow was made of steel (68). The steel bow was an Indian convention—less flexible than a composite, but it lasted longer.

Additionally, archers used different arrow types for different occasions—a chiselled point for piercing armour or a broader head used for unprotected targets (68). In this painting, as the men are fighting an animal, they would be using arrows with broader points. According to one source, a skilled archer could fire over 6 shots a minute.

The main weapon of a soldier on horseback who was fighting in close quarters, was a lace. This was closer to 10 feet long and pointed at both ends for maximum dexterity (68). In the event that this broke or was lost, men also carried a sword—a Persian shamshir, Indian tulwar, or Turkish yataghan (68).

And, as a last resort, dagger—a katar—was tucked into the belt (69). This dagger was built as a punch dagger for thrusting and had a guard to protect the hand and forearm. These can be seen tucked into the sash of almost every man who is fighting with a sword in this painting.

Another notable aspect of this particular painting is the presence of a musket. The gun was used within the Mughal Empire right from the time Akbar’s grandfather, Babur, established it. However, under Akbar’s reign, they were significantly improved and came to closely resemble the contemporary European design—much more durable and may have been better (48). Given that the Mughals places such high value on accuracy, the guns were designed as such.

In most Mughal miniatures, there is some form of calligraphy and this painting is no exception. Sometimes it is used by artists just to sign their names. However, it is important to remember that calligraphy was seen as one of the most revered forms of art in the Arabic world (Rahman, 237). It was often viewed as devotional and as having a divine connection. Calligraphy acquired the reputation for being a representation of Islamic faith in some ways. When creating a painting, the process begins with the calligraphy first. Therefore, although the content of the painting was itself important, the calligraphy is prominently displayed—it seems as though there is room created in the painting especially for this particularly treasured art form.