Legebokoff, Shelby. “Essay: The Mughals vs. The Afghans.” The Akbarnama Project, edited by Hussein Keshani, 2017. (url to come).

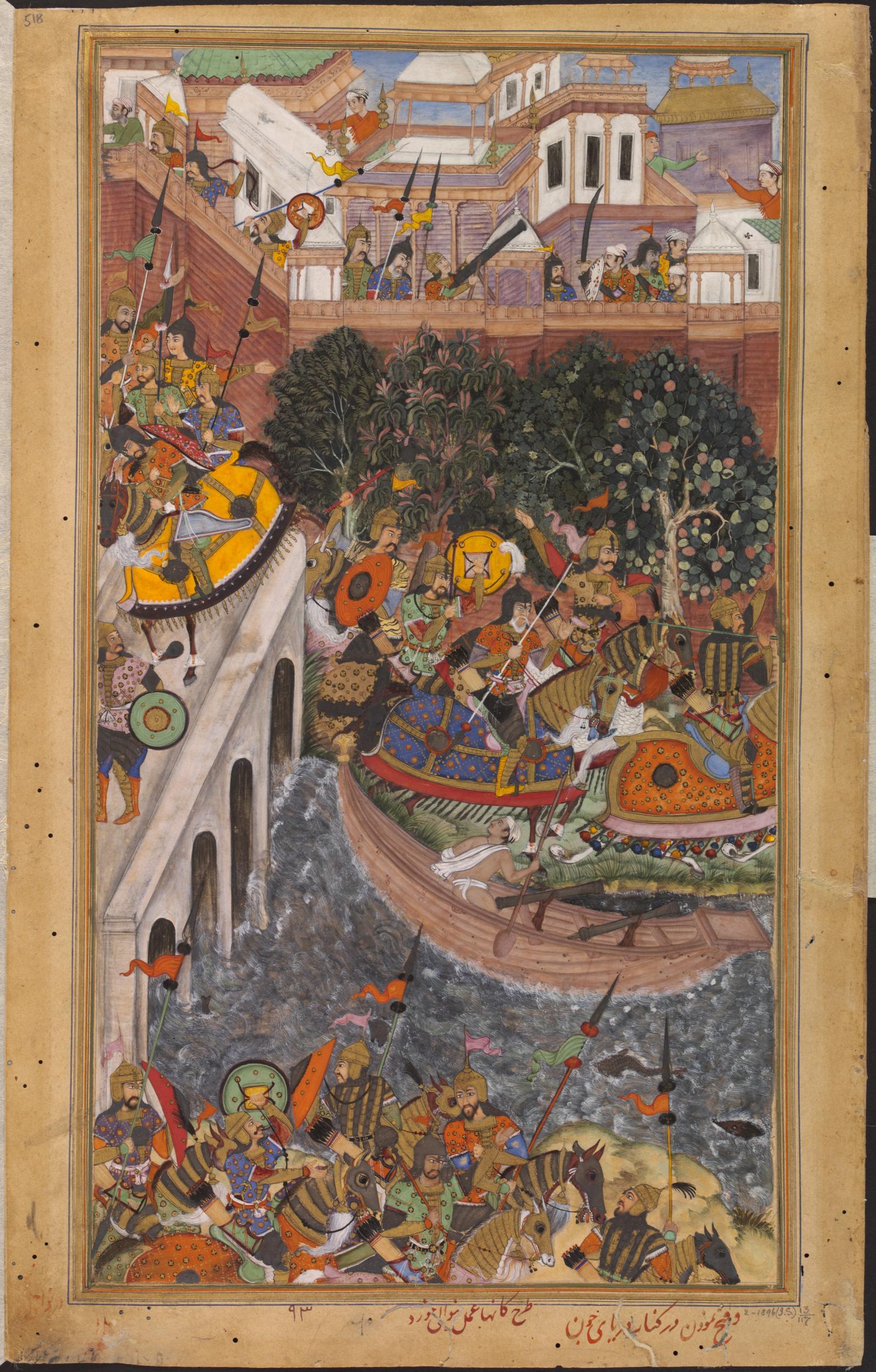

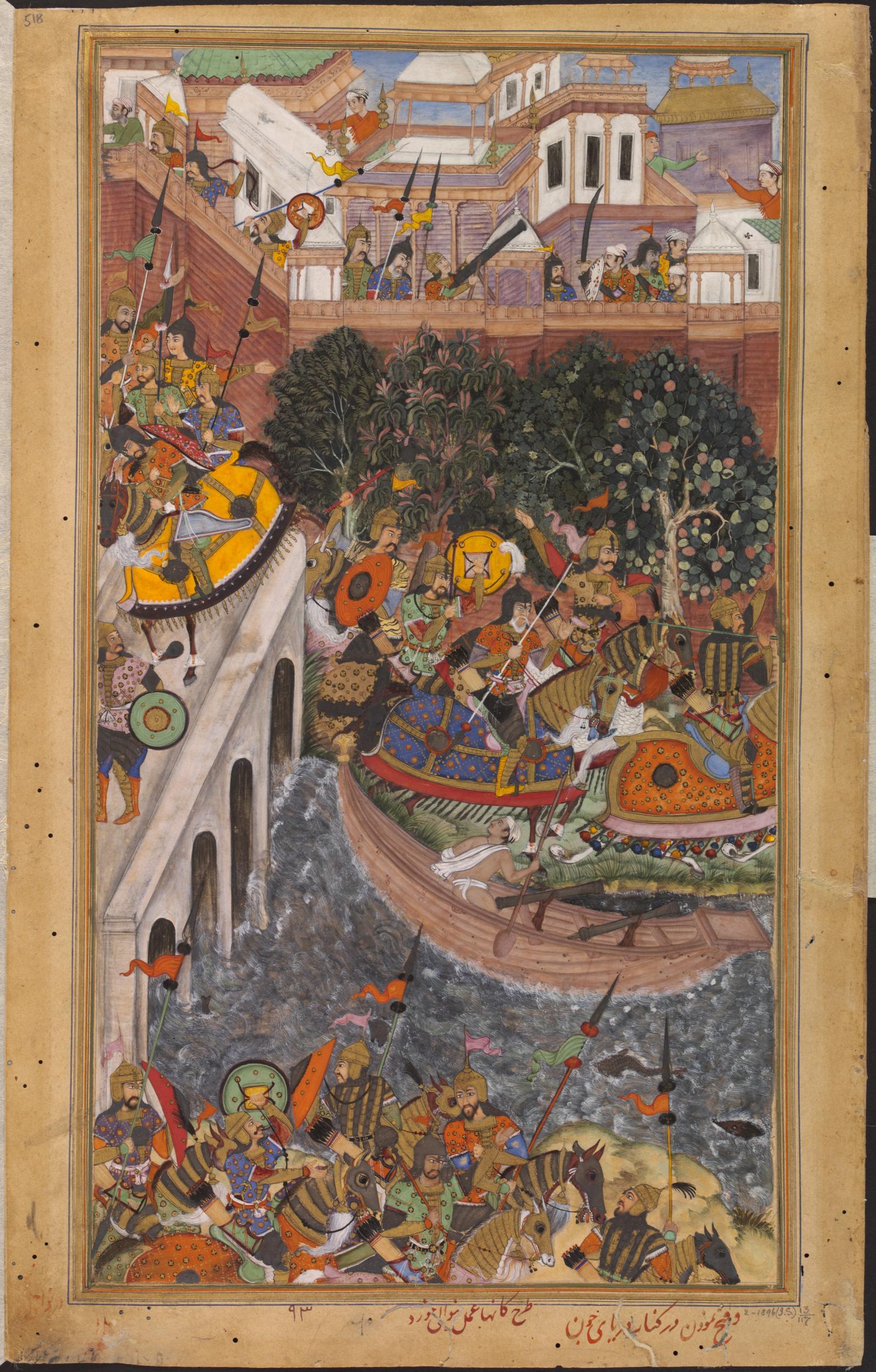

The scene depicted in folio 13 of Abu Fazl’s Akbarnama represents the victory of Khan Zaman over the Afghans. It was the Afghans who marched with great force and encamped along the banks of the Gumti river, while Khan Zaman paid no attention and kept his men in order and readied for battle. As grand heroes fell, the Afghans brought a new body of brave men to fight, driving the victors into the city. This chaotic scene is demonstrated in folio 13 of the Akbarnama and shows the victors being driven into the city walls of Jaunpur. The Afghans then turned in the other direction with the taste of victory. Only after they turned in the other direction did Khan Zaman come from behind them to destroy their success.

The image is centered around Khan Zaman on horseback near the Gumpti river. On all sides of the river soldiers are readied for battle. The scene takes place in the city of Jaunpur, which was seen as the leading intellectual center in northern India under the Sharqi dynasty.jaunpur Asher shares information regarding sub-imperial palaces that still remain in the region (282).

Three Akbar-period palaces have survived and one resides in the city of Jaunpur. It was also noted that the city of Jaunpur was of prime military importance until it fell later in Akbar’s reign (Asher 282). The lavish paintings of the Akbarnama demonstrate a strong sense of place in the northern Indian landscape. This reflects Akbar’s role as a divine king, moral architype and distributer of justice, but also as a ruler familiar with the ecological balance of land and its people (O’Hanlon 898). The name “Jaunpur” is derived from a famous rishi, Jamadagni, and the place was earlier named Jamadagnipura (Singh 89). The city is famous for its various cultural heritage sites, and devotional places, with the Gumpti river being the city’s major water source. The ancient atmosphere of Jaunpur was chaotic due to the fighting for power, until it was adopted by the Sharqi dynasty in 1393. During this period the Jaunpur Sultanate became an important military power in northern India, only to later be captured by the Mughals.

The Mughals moved south from Kabul around the sixteenth century and finally formed Delhi as their royal capital. The first six emperors of the empire differed widely in their ruling approach. Though they differed, they all used minor aspects of existing society and its institutions and local/communal leaders to incorporate into their own governing structures (Schaffer 7). The Mughal emperor Akbar is remembered today for his lasting empire that was built upon military successes. His adoption of bureaucratic practices as well as appreciation for human diversity strengthened the state. Along with Abu Fazl’s Akbarnama, many extravagant paintings were produced to accompany the histories. They displayed not only Akbar’s vitality as a warrior, hunter, and commander of elephants, but also his dynamic presence amongst his subjects (O’Hanlon 898). Mughal India belonged to a group of three called the Islamic Gunpowder Empires; along with the Ottoman and Safavid. It was at the first battle of Panipat in 1526, where the Afghans were defeated despite their superiority in numbers, due to their lack of gunpowder weapons. This defeat would fuel a series of battles to come.

The Afghans inhabited northern India as early as the late 13th century and thrived until the invasion of Babur when the Mughal empire was created. They originated from a Turkic tribe, whose name originated through the adoption of Afghan habits and customs. Historical literary importance of the Afghans grew in connection with their migration to India, where they encountered different forms of social religious, and political organization (Green 172). It was the Afghans defeat and steady integration into the Mughal state after 962/1555 that brought a new importance to the question of Afghan self-definition (Green 172). The setting for the Afghans was a large number of settlements across northern India, due to patronage of migrant workers as well as migration strategies, all under the support of the Afghan Lodi. Though migration strategies are unclear, it was said that in many cases migration was a result of military prospect, or the search for agricultural land (Green 174). The elite class demonstrated interactions with the cosmopolitan Persianate culture in India, but with the conquests of the Mughals these diversions of Afghan culture were brought to a halt. Alam describes how flourishing Afghan towns turned desolate from the fear of Mughal invasions of the regions, as well as the punishment experienced by those held captive to Mughal soldiers (75). Though a short-lived state of Afghan power did exist under the Sur dynasty, they were finally transposed by the dominating ethic group of the region (the Mughals). It was after the development of this plural religious state structure by the Mughals that forced the Afghans to reinvent themselves through adaptation or rebellion.

The third Mughal emperor Akbar ruled over areas that were established by his grandfather Babur, such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, and northern India. In the narrated chronicle of his life, called the Akbarnama, the author Abu Fazl retells stories of war, celebration, and religion; all of which took place during Akbar’s reign. The intricate paintings of the Akbarnama represent not only Akbar as a divine ruler, but person of military importance. This can be associated with many battles between the two differing societies; the Mughals and the Afghans. Though, Afghan power was exhibited in ancient India for a brief time, it eventually gave way to the increasingly prevailing Mughal empire. This stress between cultures created many issues for each group, as well as a struggle for self-definition and pride for the Afghans. It is in folio 13 of the Akbarnama that we get a glimpse into one of these battles, as Khan Zaman and his army defeat the Afghans once again.

TEXTS