DeMille, Tanis. “Essay: The Flight of Baz Bahadur” In Akbarnama: A Digital Art History Student Project, April 4, 2018.

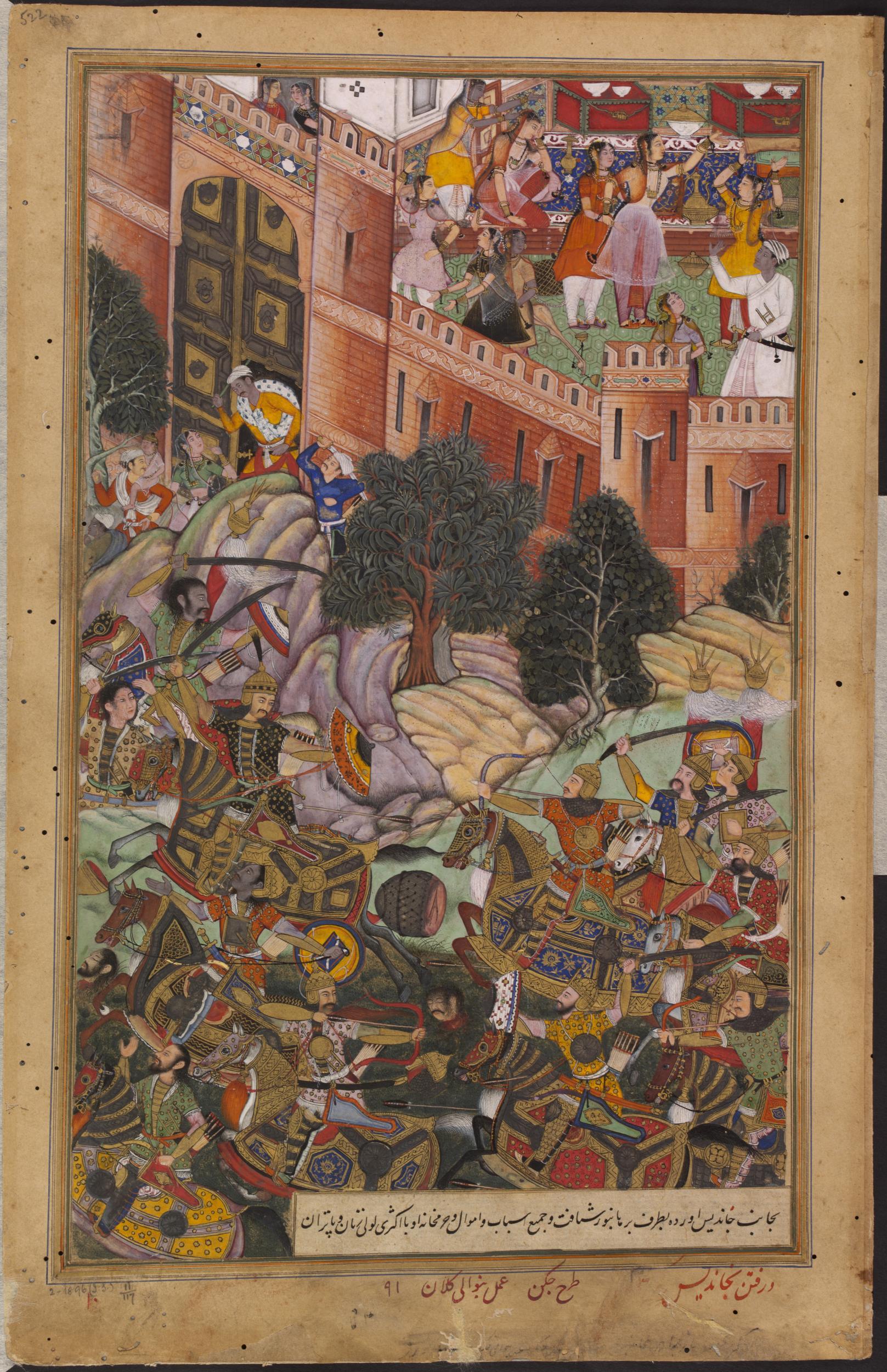

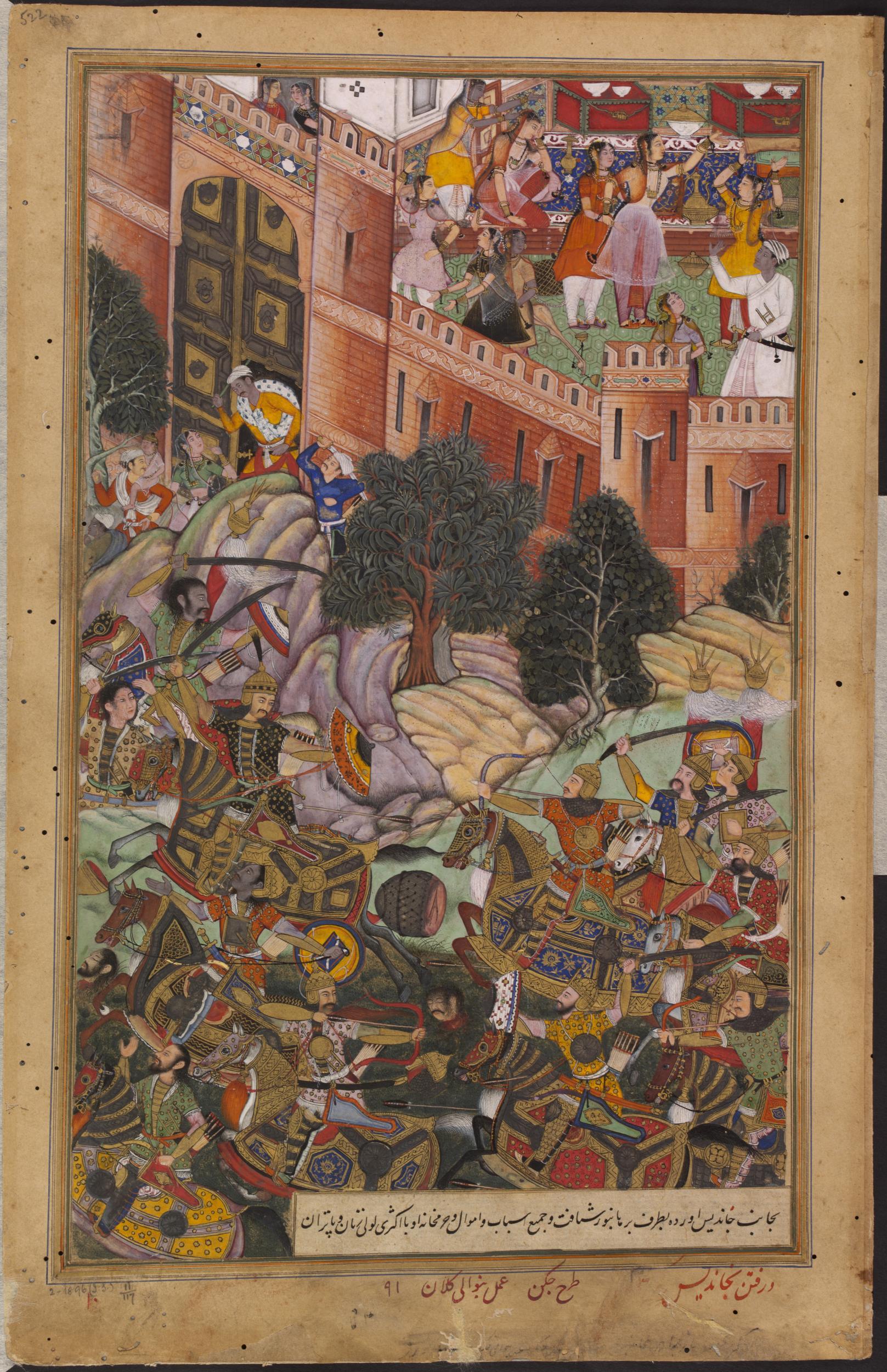

The Akbarnama, created by Abul Faz’l, details the takeover of Malwa by Akbar’s troops and their leader, Adham Khan. It was created by Jagan and Qabu between 1590 and 1595. The painting is done in opaque watercolour on gold paper, and truly speaks to the skill of the Mughal artists and painters.

In the painting Baz Bahadur is depicted on a horse fleeing from the scene of the invasion. He is adorned in black and orange armour, and is carrying a sword and shield. Just to the right of Bahadur, Adham Khan, dressed in vibrant orange armour, is posed aiming an arrow at Bahadur. When looking at the painting it is interesting to distinguish Bahadur’s troops and Khan’s troops in the mix of men. At the very top of the painting Rupmati, Baz Bahadur’s lover is depicted with other hindu women on a balcony. Some women on the balcony are watching the events below, while others are comforting Rupmati who is crying out of heartbreak for the loss of Bahadur. The Hindu women are all adorned in traditional clothing, displaying a vibrant range of pinks, yellows, and oranges. This painting excels in demonstrating the conflict between Khan and Bahadur, and provides some insight into how to event played out. It also shows some of the deep history that surrounds Malwa, and its surrounding areas, which are important in later history.

After the death of the Emperor of Malwa, Shuja’ Khan in 1554, his eldest son, Bayazid Khan assumed the government under the title of Baz Bahadur. His brother Daulat Khan asserted a claim to a share in the Kingdom, and obtained the support of the Sarangpur division of troops. Under the vise of paying his brother a visit for condolence, Bahadur marched to Ujjain and murdered his brother, displayed his head on the gates of Sarangpur. Bahadur next turned his attention to his brother Mustafa Khan, who after several defeats, fled Malwa, leaving both Raisin and Bhilsa open to Bahadur’s occupation.

The Gonds succeeded in their disastrous campaign against Malwa, and the Malwa army was almost completely annihilated. Stung with the shame of this defeat, Bahadur retreated and abandoned himself to dissipation and sensual ease. Taking advantage of the distracted state of Malwa, the Great Emperor Akbar, dispatched an army under Adham Khan in 1560. Bahadur heard nothing of the movement of these troops until it was within a short distance to the capital. He hastily gathered troops and advanced without order to battle. After displaying great bravery, his troops proceeded to desert him, forcing him to flee Malwa and his lover Rupmati, leaving Adham Khan to occupy the country. (King, 396-397) According to legend, Bahadur escaped Malwa by a rope through the window of his palace. (Ray, 89)

Baz Bahadur had a mistress, Rupmati, who is said to have been one of the most beautiful women ever seen in India. Bahadur was a great lover of music, of which he channelled for Rupmati, and composed many songs dedicated to her. (Lane-Poole, 245) Their love has become so notoriously well known that it has been handed down to posterity in song, and many stories still told to this day. (King, 396) She was as accomplished as she was beautiful, and was celebrated for her verses in the Hindi language. After the flight of Baz Bahadur, she fell into the hands of Adham Khan. (Lane-Poole, 245)

Upon hearing of Rupmati’s great beauty, Khan had been determined to take her into his harem. (King, 397) Unable to resist his solicitations and threatened violence, she was to give herself to him for an hour. It is said that she put on her most beautiful dress, on which she adorned with her most magnificent perfumes, and lay on the couch with her mantle drawn over her face. Her attendants thought she was asleep, but when they tried to wake her upon the arrival of Adham Khan, they were shocked to see that she had taken poison and was already dead. Adham Khan had possession of the other ladies in Baz Bahadur’s harem, and when Akbar himself rode into Malwa to stop Adham Khan’s atrocities, Maham Anaga had the women killed, so that they could not tell the tale to Akbar. (Lane-Poole, 245)

It is said that Akbar was incredibly displeased with Khan, as he had kept all of the spoils of victory to himself, including Bahadur’s singing girls. Akbar thought it best to visit the conquered province himself. It took Akbar sixteen days to arrive in Malwa, and was in Sarangpur by the time Khan found out he had left Agra. Adham Khan was recalled after Akbar’s arrival in Malwa, and Pir Muhammed was nominated the Governor of Malwa in his place.

In 1561, Pir Muhammed marched against Burhanpur, which he captured, killing all of its inhabitants. Bahadur, who was nearby, coordinated the overthrow of Muhammed with Tufal Khan, the Regent of Berar, and Miran Mibarik Khan of Asir. The confederates routed Pir Muhammed, who drowned in the pursuit, and drove Mughal troops out of Malwa. Because of this, Baz Bahadur was restored to the throne of his kingdom. Though, Bahadur was not on the throne long because Abdullah Khan Uzbeg, one of Akbar’s officer, reoccupied Malwa and compelled Bahadur to seek asylum in the hills of Gondwara in 1562. Baz Bahadur made occasional raids from his mountain hideaway, and was sometimes able to secure temporary possession of small districts. After approximately ten years, Bahadur grew tired of a wandering life filled with guerilla warfare, and in 1570, surrendered to the Emperor. The Emperor gave Bahadur a commission as commandant of two thousand cavalry, but Bahadur died not long after. (King, 397-398)

The principle fort-city of Malwa is Mandu, which is 25 km south of the city of Dhar and situated on a high hill. Because it is on a hill amidst beautiful views, the Muslim rulers termed Mandu as the Shahidabad or the ‘city of joy.’ During the sixth century the Rajput King Ananda Deo constructed the fort in Mandu. Because of the great history of Baz Bahadur (A Sultan of Malwa) and Rupmati’s love, the legend and the stories are told to this day in Mandu. After his conquest of Malwa, Akbar visited Mandu several times but was not attracted to the city. Jahangir on the other hand was incredibly impressed by the scenery and architectural beauty and recorded it into his autobiography. In 1732, the Maratha leader Malhar Rao Holkar defeated the Mughal administrator in Malwa and subsequently established a new capital at Dhar. Consequently, Mandu was abandoned. The old fort of Mandu, the Budhi Mandu, can still be seen in the ruins in the hill on the Western side of a dense forest. (Ray, 86-89)

Malwa flourished under Mughal rule, especially in terms of agricultural and industrial production. It quickly became one of the best revenue-yielding provinces in the empire. The Marathas started raiding the province during the closing years of Aurangzeb’s reign, and the province suffered greatly because of the recurring attacks. The Mughal emperor Muhammad Shah was compelled by the increasing Maratha pressure, to appoint Peshwa as deputy-governor of Malwa and hand over the province. Malwa was then divided between the Maratha generals whose descendants held most of it until 1947. From 1780 to 1818, once British rule in India had been firmly established, the province became one of the principal arenas in which Muslim, Maratha, and European troops contended for control of the empire. (Haig and Islam)